Top 10 Drought Management Tips

For Your Cattle Pastures

1 2

Image Credit: Shever

With the exceptionally dry growing conditions that many farmers experienced this summer, I've dedicated this article to reviewing the top 10 drought management strategies for cattle farms. Half of these strategies are for the dry years to lessen the toll that drought takes on your pastures and half are strategies to implement during good years to prepare your pastures and your farm business to be more drought resistant in the future.

Average growing conditions are actually pretty rare!

When the weather hits extremes the news media typically has a field day feeding us endless stories of shock and awe about the unexpectedness and magnitude of the swing away from the year's "normal" rainfall and temperature. But as cattle farmers who rely on the land (and the weather) to provide feed for our cattle, we need to set aside this wide-eyed wonder at extreme weather. Weather extremes are normal. Plan for it. Stop expecting average weather!

Average weather is defined by its extremes. Our expectation of average weather is "created" by adding up all the weather extremes that swing either side of the middle.

A truly average year is actually pretty rare - less than once every 5 to 10 years, on average... By contrast, a "normal" year includes not only the mathematical average but also all the years on either side of average, including the years when weather reaches extremes.

Tree rings can tell you about the range of weather patterns that are normal in your area

Have you ever taken the time to study tree rings from some of the really really old trees in your area? You might be surprised at what you can learn about the range of growing conditions you need to plan for in your grazing management strategy.

It's one thing to theoretically know how much your local climate can vary from year to year; it's quite another thing to actually see that variation play out in tree growth rings from year to year over the course of centuries.

You be wondering what tree growth rings have to do with the grass in your pastures. Well, growing conditions that are good for trees are generally also going to be good for grass. The same is true for poor growing conditions. But, while grasses are annual and therefore don't preserve a physical record of prior years' growth conditions, trees do. Tree rings are therefore a fantastic proxy for the broad range of growing conditions you need to plan for in your grazing management strategy.

Image Credit: Jason Hollinger

I recently had the opportunity to see some freshly cut stumps from several extremely old pines close to where I live, each more than 150 years old. One thing that stood out was a repeating pattern of approximately 30 years of wide growth rings followed by 30 years of narrow growth rings, which corresponds remarkably well with historic records in our valley showing a repeating pattern of approximately 30 years of hot dry summers and cold winters followed by 30 years of cooler wetter summers and milder winters. These tree rings would suggest that our local climate is now a few years into the next 30-year cycle of hotter, drier summers and colder winters.

But what also stood out for me was just how much variation there was from year to year within each of these longer cycles. Some tree rings showing virtually no growth at all, which must have been some truly extreme years to experience. Others showing extreme growth surges well outside the norm - a virtual farmer's paradise.

Nor was any extreme year automatically followed by a return towards the average - sometimes whole clusters of extreme years hint at droughts lasting many years or, on the other extreme, idyllic growing conditions lasting so many years that had we been there to experience these years through the lens of our own limited human perception of time it would have given us the false impression that these idyllic growth conditions were the new normal, only to have them wiped away again as the climate pendulum finally, inevitably, swung away again in another direction.

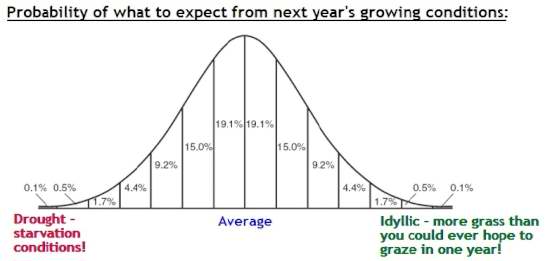

In other words, the "normal" year is a myth because there is no such thing as a single "normal" year. In reality a normal year is simply any one of the possible weather conditions from drought to average to idyllic along a sliding scale, as represented in the chart below.

This chart shows all the growing conditions that are "normal" in your area. The probability curve shows how often each occurred over many centuries, much like adding up tree rings of different widths.

This chart shows all the growing conditions that are "normal" in your area. The probability curve shows how often each occurred over many centuries, much like adding up tree rings of different widths.The bell curve of the graph represents the frequency (and thus the probability) of experiencing any one of these conditions in any single year. The wilder the swings in weather in your area, the flatter and more stretched out this probability graph will be.

Although probabilities favor that next year's weather will be closer to "average" (maybe only a little bit drier or maybe only a little bit wetter), realistically it can fall ANYWHERE along this scale. Given a large enough number of years, you WILL experience all of the possibilities at some point in time. So, since anywhere along the scale is possible in any given year (even if some have a higher likelihood of striking than others), we really should choose to be prepared instead of surprised when one of the extremes does strike.

So, let's look at the Top 10 Drought Management Tips for grazing during drought years...

The top 10 drought management strategies listed below are split into two parts.

The first five tips are for the dry years to help you maximize pasture growth and minimize soil evaporation during a drought, and to help you protect the grass species in your pastures so they recover faster when the drought finally ends.

The second five tips are for the good years to help you prepare your pastures to be more drought resistant in the future.

Tips 1 to 5 (drought survival)

1. Divide your pastures into DAILY GRAZING SLICES with the help of portable electric fences.

Switch to using daily grazing slices to maximize pasture recovery periods between grazing intervals. As an example of how this works, imagine it takes 90 days to do a full loop around your grazing rotation. If that loop is divided into 9 pastures (10 days per paddock), then your grass (and soil) has 80 days of undisturbed growth and 10 days of grazing and trampling and churning by cattle feet. On the other hand, if you use daily grazing slices, your grass gets 89 days of recovery between grazes - a whole 9 extra days of undisturbed growth!

There's an old saying that "a cow's feet consume twice what her mouth does."

Daily pasture slices will also minimize the amount of grass that is wasted to trampling and churning by cattle feet. The first thing cattle do when they get into a fresh grazing slice is eat. By the time they are ready to wander about and explore the paddock or bed down to sleep or chew their cud, the bulk of the grass has already been eaten and won't be wasted to cattle traffic. On the other hand, when using larger multi-day pasture slices a massive amount of valuable grass will be wasted by trampling because cattle don't just freeze and stand still once their bellies are full.

When you switch to using daily grazing slices your cattle's behavior during grazing will also change. The small daily pasture slices will force cattle to bunch more tightly together during grazing and, since all the good grass will be all gone by the end of the grazing day, it creates intense competition within the herd. This causes the cattle to begin grazing as a mob as the cattle enter into a fierce competition with one another for the best grass. Daily grazing slices eliminate the luxury of grazing as a bunch of picky selective individuals.

This change in cattle behavior creates a much more consistent grazing impact on your pastures so that all grass species are grazed equally rather than the best plant species being grazed right to the ground before the less tasty grass species are touched. Thus, daily grazing slices are an important strategy for protecting your best plant species against overgrazing during a drought.

Daily grazing slices also ensure that your cattle's feed quality stays consistent from day to day during the drought because they get top quality fresh pasture every day instead of top-grazing the best grasses on the first day after a pasture move and then facing deteriorating nutrition every day until the pasture finally runs out and they are moved again.

You can learn the most efficient way to combine portable and permanent electric fences for a daily grazing rotation in the article series about the smart electric fence grid. And in the core grazing rules article series you can learn about even more benefits of using daily pasture moves.

2. Leave a tall 6 to 10 inch stubble after grazing.

As I mentioned in the previous tip, switching to using daily pasture slices will cause cattle behavior to change (they begin grazing as a mob). This in turn means that the stubble left behind when your cattle move on to the next pasture slice will be much more uniform in height than when using larger less frequent pasture moves. And, by simply varying the size of each day's grazing slice, you have a huge amount of control over how tall that stubble will be.

A tall stubble is your lifeline during a drought.

A tall grass stubble ensures that there is a tall buffer of remaining plant material to shade the soil and reduce air movement (wind) across the soil surface, both of which are vital to reduce moisture losses in the soil and thus reduce the severity of the drought in your pastures.

That stubble and the shade it provides also helps to keep the soil surface from becoming a sun-baked hard-pan so that the soil can quickly absorb even small amounts of rainfall instead of losing that rainfall to evaporation or runoff. When it does rain a little bit, the tall stubble gives the soil some shade to slow surface evaporation to give the rain more time to soak in before it evaporates. The stubble also serves as an obstacle for puddling water to give rainfall more time to soak in before it runs away down-slope.

Every drop of rain counts during a drought - a tall grass stubble is your primary defense system to take full advantage of even very minimal rainfall so it is not lost to evaporation and runoff before it has time to soak in and actually do some good.

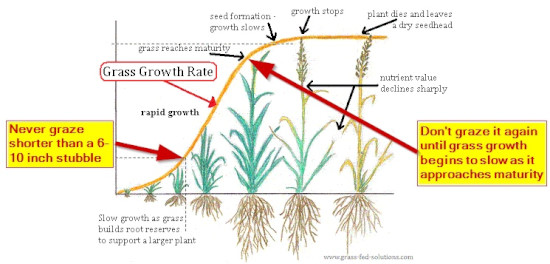

And in case you were wondering, leaving behind a tall grass stubble is not a waste of grass. The grass left behind after grazing will have deeper root reserves, which means that your pasture grasses will be able to access moisture deeper in the soil than if you had grazed the grass shorter. Furthermore, root volume tends to mirror above-ground plant volume because roots die back after grass is grazed. Grass that is grazed really short will initially grow quite slowly until it gets to be about 6-10 inches tall; that's the height at which the root reserves regain a critical mass to support faster plant growth, as illustrated in the image below.

Grass growth rates vary greatly depending on plant maturity.

Grass growth rates vary greatly depending on plant maturity.Leaving a tall grass stubble means that grass doesn't have to go through that slower growth phase while it rebuilds its root reserves - a tall stubble ensures that it can carry on growing as fast as possible, thus helping maximize grass productivity over the whole season and reducing the time it takes before you can re-graze the pasture again. This concept is explained in detail in the first article in the core grazing rules article series.

3. Combine your herds into as few groups as possible.

Combining your herds into as few groups as possible has a wide range of benefits. The larger the herd, the more of a mob-grazing effect it creates, which means you get more efficient use of your pastures (more even grazing pressure to the plant species in the pasture mix and a more consistent stubble). A larger herd also reduces your management costs (less electric fences and less herds to move every day). And combining your herds also makes it much easier to budget your grass reserves and calculate ahead to make sure that your grazing herd is moving slow enough to give the grass time to recover fully between grazing passes.

4. Feed some hay to let your pastures catch up.

This tip is designed to give your pastures a break so you can maximize grass growth rates.

As pasture yields begin to deteriorate during a drought, the grazing rotation will begin to catch up to itself, either forcing farmers to graze each pasture harder (shorter than the ideal 6-10" stubble) or to graze it sooner before the grass growth reaches maturity.

If farmers opt for grazing each pasture harder by leaving a shorter stubble, that not only slows grass growth, but also compounds the drought problem by exposing the soil to higher rates of soil moisture evaporation.

On the other hand, if farmers choose to re-graze their pastures sooner before the grasses have reached maturity, then that also will reduce pasture yields because you're not taking advantage of the full time period when grass growth rates are maximized.

Here's another look at the image from the second tip - notice how grass growth rates don't drop off until the plant reaches maturity. Maximizing pasture productivity is about timing grazing so that your herd returns just as the pasture reaches maturity and then only grazes it sufficiently to leave behind a tall 6-10" stubble so rapid growth can continue immediately after grazing.

Maximize pasture yields by grazing as soon as grass reaches maturity (not before, not after), and always leave behind a tall grass stubble so maximum growth rates can resume immediately.

Maximize pasture yields by grazing as soon as grass reaches maturity (not before, not after), and always leave behind a tall grass stubble so maximum growth rates can resume immediately.Once the grazing rotation begins to catch up to itself the unprepared farmer has to pick between two bad choices - graze sooner, or graze each slice harder. Either choice sets off a vicious cycle of further drops in pasture yields and increases soil moisture evaporation and plant degradation.

The prepared farmer, on the other hand, will tap into his hay reserves (hopefully he has a drought reserve, discussed in tip #6 below) to feed some hay to his cattle for a few weeks to give the pastures a little extra time to keep growing before resuming the grazing rotation.

A few weeks of hay fed early in a drought season will pay huge dividends by increasing pasture yields and protecting soils from more severe drought. It may also be the dividing line between whether you have to start selling cattle to make it through the drought.

Feeding hay on pasture to give the grazing rotation time to catch up.

Feeding hay on pasture to give the grazing rotation time to catch up.Image Credit: Dave Young

5. De-stock early.

At some point it will become clear that your pastures won't suffice and you may need to sell off some cattle to make it through the drought.

Start selling early.

A 10% reduction in your herd size early in a drought may well tip the pasture yields back to sustainable levels and save you having to sell off 25% or more of the herd at a later date.

But the natural reaction is to wait and hope while the hungry mouths of your cattle herd continue plowing through your diminishing grass reserves and the grass stubble gets so short that the drought has a much more severe and long-lasting impact on your pastures. Then, when the situation reaches a critical stage, you'll be left selling cattle when prices are especially low because all your neighbors will also be flooding the markets with their cattle. And your brood cattle may be left so thin that even if they survive, their conception rates may be disastrous in the next breeding cycle (see this article about body condition scores for more information about how letting cattle get too thin can have dramatic consequences to conception rates even many months after your cattle have regained their lost fat reserves).

If you suspect a potential grass shortage, de-stock early while prices are still high and when trimming a few poorer quality animals from your herd may be all it takes to stay ahead of lower pasture yields. A small herd size reduction early on can usually be accomplished by selling a few lighter meat animals and by culling your least productive animals (cows that you've flagged as having a history of calving difficulties, health issues, poor feed conversion, or poor quality calves). Waiting until later means you'll have to bite far deeper into your prime brood animals and sell animals that are the long-term bread and butter of your business.

Page 1 / 2